Author: CORD Individualized Interactive Instruction Task Force

Click HERE for PDF version of document

Introduction

Emergency medicine (EM) resident education is evolving. Whereas teaching was once confined to five hours of weekly didactics, residencies are frequently turning to other formats in the pursuit of creating more effective, engaging learning environments, while incorporating innovations in teaching. The CORD Individualized Interactive Instruction (III) Task Force was created to identify best practices in asynchronous learning, and provide guidance around RRC-EM guidelines to ensure compliance.

The members of the task force, having surveyed the CORD membership, have created this document to showcase those best practices currently in place at a variety of EM residencies, and to highlight how these programs are addressing RRC requirements. This document will be a living one, with new best practices added as innovation continues. Note that this document reflects a consensus of task force members, and has not been vetted or approved by the RRC-EM.

The task force members hope the CORD community finds the information useful, and we remain available for further clarification going forward.

Jeffrey Siegelman, MD (Emory University, III Task Force Chair, jsiegelman@emory.edu)

Claudia Barthold, MD (University of Nebraska Medical Center, III Task Force Vice Chair)

Contributing Authors: Ben Azan, Claudia Barthold, Bo Burns, Esther Chen, Steve Ducey, Jay Khadpe, Chaiya Laoteppitaks, Sam Luber, Maria Moreira, Jane Preotle, Jeffrey Siegelman, Kimberly Sokol, Britni Sternard, Robert Tubbs, Laura Welsh, Nathan Zapolsky

Structure

2015 Survey Data

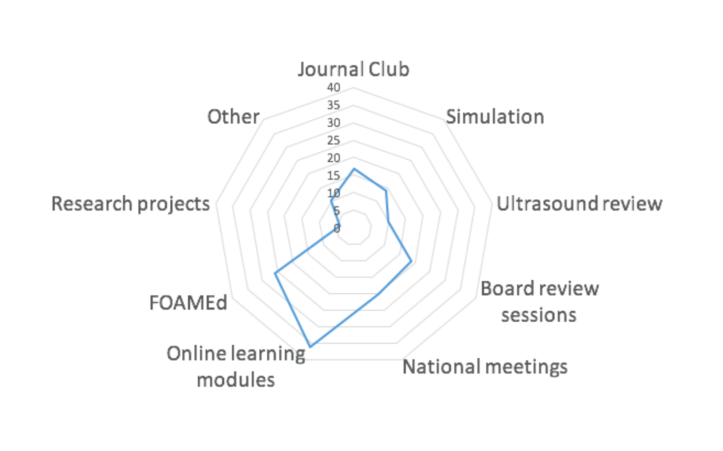

- 67% of programs responding are using III.

- About half of those using III have changed to a 4 hour didactic day.

- This is the distribution of activities programs are utilizing for III:

Best Practices - National and Regional Meetings

Description: Attend lectures, workshops, or didactics at national/ regional meetings relevant to EM or the EM subspecialties. Presumes that the presentations would be “synchronous quality.”

Monitoring Participation:

- Check in with attending at the presentation

- Sign in sheet/log in New Innovations

- In person supervision

- CME certificate turn in or certificate of attendance

- Self report of which they attended

Faculty Oversight:

- Faculty in the room with them

- Discussion post conference with faculty

- Guided EBM review post-conference and homework project

Monitoring for Effectiveness:

- Post conference discussion

- Residents surveyed when logging credit

- Annual review of the activity by the PEC

Evaluation Component:

- Verbal discussion post conference

- Reflective writing on lessons learned from attending a session

- Postactivity quiz given/graded by faculty who also attended

- Resident has to present new information in didactics

Compliance Pitfalls:

- Honor system for attendance misses interactive component

- CME forms or attestation pages do not rise to the level of III on their own

- Relying on self reporting to RMS or filling out a post conference eval as only method of evaluation

- PD oversight questionable at non-EM or some international meetings: Limit credit to conferences attended by residents with EM faculty

- Sign-in sheet does not indicate presence at the entire meeting

Best Practices - Simulation

Description: Residents participate in small group or individual simulation sessions outside of regular conference time with direct faculty oversight.

Monitoring Participation:

- PD may be physically present during sessions

- Participation is monitored electronically using residency management software

- Attendance sheet is submitted to PD

Faculty Oversight:

- Direct faculty supervision during session

Monitoring for Effectiveness:

- Annual review of the activity by the PEC

- Solicit written feedback of the activity from both residents and supervising faculty

- Residents surveyed when logging credit

Evaluation Component:

- Supervising faculty provides verbal feedback of the resident during debrief

- Supervising faculty provides written feedback of the resident

Compliance Pitfalls:

- Tracking participation by residents using attendance sheet or procedure tracking software, on its own, is insufficient

- Difficult to monitor for effectiveness unless feedback is solicited from participants. Residents on PEC or self study team can help.*Note that other directly observed activities including journal clubs and teaching activities can be used in a similar way.

Best Practices - FOAMed Resources

Description: Numerous blogs, podcasts, and other activities are available online. While the FAQs specifically state that listening to a podcast does not rise to the level of III, a number of programs have developed strategies for making these activities interactive and compliant. The most commonly used resource is the ALIEM AIR series (Lin M, et al, J GME 2015) , with many others in use as well. While the AIR series is a compilation of vetted online resources, programs report varied efforts to evaluate the content available on other sites.

Monitoring Participation:

- Quiz (AIR series quiz completion and score can be verified by PD’s of enrolled programs)

- Faculty attestation of discussion with resident

- Attendance at discussion session

Faculty Oversight:

- Testing/Quiz

- AIR series quizzes

- Blog

- Faculty review of resources

- In-person discussions

Monitoring for Effectiveness:

- Annual program review

- Faculty review of content

- Residents surveyed when logging credit

Evaluation Component:

- Quiz (most common)

- Online discussion (via Skype, comment postings, etc)

- Senior resident discussion session of CME questions offered by the activity

Compliance Pitfalls:

- Not monitoring effectiveness

- A quiz alone is insufficient for the interactive component.

- Some sites rely on forums/blogs for interactive component which are used variably.

Best practices - Online Resources

Description: Multiple online platforms are available which have the same limitations as FOAMed resources with respect to the interactive component. Multiple programs use these activities, and all must add to them to rise to the level of III. Some examples are below:

- Qbanks: Rosh Review, MD Challenger, HippoEM

- Assigned articles: CDEM, EMed Home

- Modules: CITI Certification, NIHSS traing, IHI modules

- SonoSim Modules

Monitoring Participation:

- Question completion (end of articles, qbanks, faculty written)*

- Writing quiz questions based on articles read

- Discussion boards, twitter accounts

- Attendance at discussion of CME questions

- Turn in writeup about pearls learned or quick summary*

- Brief review of content during didactic time

*Must still add interactive component

Faculty Oversight:

- Active faculty presence and oversight in sessions

- Faculty review of content

- Faculty led discussion sessions/didactics

Monitoring for Effectiveness:

- PEC review

- Residents surveyed when logging credit

Evaluation Component:

- Quiz scores

- Evaluation of participation in discussions

- Reviewing quiz questions written by residents

- Discussion with faculty/in conference

- Evaluate and discuss writeup about article read

Compliance Pitfalls:

- Limited interaction with faculty by online means.

- Using automatic PD notification or attestation certificates do not meet RRC guidelines

- Online forums must be monitored and responded to by faculty to rise to level of III

Published Literature on III and Asynchronous Learning

- Ashton A and R Bhati. The use of an asynchronous learning network for senior house officers in emergency medicine. Emerg Med J 2007;24:427–428.

- Burnette K, et al. Evaluation of a Webbased Asynchronous Pediatric Emergency Medicine Learning Tool for Residents and Medical Students. Acad Emerg Med 2009; 16:S46–S50.

- Chang T, et al. Pediatric Emergency Medicine Asynchronous Elearning: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Solomon Fourgroup Study. Acad Emerg Med 2014; 21:912–919.

- Della Corte F, et al. Elearning as educational tool in emergency and disaster medicine teaching. Minerva Anestesiol 2005;71:18195.

- Gisondi M, et al. Adaptation of EPECEM Curriculum in a Residency with Asynchronous Learning. West J Emerg Med. 2010; 11(5):491498.

- Jordan J, et al. Asynchronous vs didactic education: it’s too early to throw in the towel on tradition. BMC Medical Education 2013, 13:105.

- Lin M, et al. Approved Instructional Resources Series: A National Initiative to Identify Quality Emergency Medicine Blog and Podcast Content for Resident Education. JGME 2016; 8(2): 219225.

- Liu Q, et al. The Effectiveness of Blended Learning in Health Professions: Systematic Review and MetaAnalysis. J Med Internet Res. 2016 Jan; 18(1): e2.

- Lund A, et al. Disaster Medicine Online: evaluation of an online, modular, interactive, asynchronous curriculum. CJEM. 2002; 4(6):408413.

- Mallin M, et al. A Survey of the Current Utilization of Asynchronous Education Among Emergency Medicine Residents in the United States. Acad Med. 2014;89:598–601.

- Reiter D, et al. Individual Interactive Instruction: An Innovative Enhancement to Resident Education. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61:110113.

- Sadosty A, et al. Alternatives to the Conference Status Quo:Summary Recommendations from the 2008 CORD Academic Assembly Conference Alternatives Workgroup. Acad Emerg Med 2009; 16:S25–S31.

[…] The CORD III Task Force recently released a blog post on “Best Practices in III.” […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] CORD EM Blog: III Best Practices Task Force Update. Available at: https://cordemblog.wordpress.com/2016/06/09/cord-individualized-interactive-instruction-task-force-u…. Accessed on January 1, […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Best Practices in Individualized Interactive Instruction. 2015. Available at: https://cordemblog.wordpress.com/2016/06/09/cord-individualized-interactive-instruction-task-force-u…. Accessed March 1, […]

LikeLike